The Ilemi Triangle: Shadows of The Four Lines on the Grassland

By Michael Lopuke Lotyam

First Issued on: 28th August, 2019

Introduction:

It should not come as a surprised to the newly independent country of South Sudan and Kenya that the conflict over the Ilemi Triangle that has lasted for a century, still remained a thorny issue between the two countries without any solution. This geopolitical struggle over the Ilemi Triangle between Ethiopia, the East Africa British Protectorate (Kenya), Uganda, and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan right from the end of 19th century was necessitated by the quest to acquire more land by each empire. The British Anglo- Egyptian Condominium Sudan was the largest of the political units created by imperialism in Africa – with an overall size to just one million square miles (2.4 million square kilometres)1. The dominant of the British position in Sudan had been formalized in the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1899, which recognized Sudan as an Egyptian possession administered by the British officials on behalf of the King of Egypt2. This meant that any decision made by the British Officials in Sudan must finally get the approval of Egypt before it becomes binding.

According to Robert O. Collins, Ilemi became a reality at a conference convened at Kitgum in Uganda in April 1924 on the initiative of Kenya officials and attended by the representative of Kenya, Uganda, and Sudan.

The main issue according to the Kenya officials was “The problem was the safety of the North Turkana”3 and their solution to the problem was to control the Ilemi Triangle which was part of the Sudan territory as per the Treaty of the Council which adopted the report of the survey carried out between 1902-3, and 1907 by Captain Philip Maud in 1914.

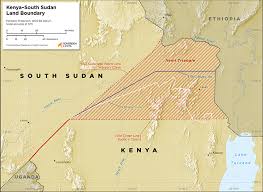

The purpose of this article is to look into how a number of administrative lines were created by the Kenya Colonial Officials in an effort to protect and safeguard the Turkana pastoralists beyond the internationally defined boundary; and in view of the current diplomatic effort between the two governments of the Republic of South Sudan and Republic of Kenya to find a lasting solution to the century-old dilemma, the paper intends to educate and inform those involved in the delimitation and dialogues among the adjacent communities and the two countries along the international boundary to respect the internationally defined boundary in accordance with the international treaties as adopted and confirmed by the Organization of Africa Union (OAU) Resolution A.G.H/16.1 of July 21, 1964, which incorporates the rule of uti possidetis: ‘All the member States are committed to respecting the frontiers existing at the time of their independence’4 and in respect to this, opt for a peaceful means of resolving the boundary issue.

Description of the Ilemi Triangle

The Ilemi Triangle is a South Sudanese territory that lies in the extreme southeastern part of South Sudan within Eastern District of Equatorial Province. It has a total area of approximately 8743 km.5 Ilemi is a triangular piece of arid hilly terrain named after the Anuak Chief Ilemi Akwon, whose village was the last Anuak (Anyuak) settlement up the Akobo River at its junction with the river Ajibur (34°20’ east longitude and 6°45’ north latitude) and bordering on Ethiopia and Uganda’s Eastern Province.6 Chief Ilemi Akwon also known as Ilembi, Milile, Ilimi,Ulimi, and Chamchar. His mother was a Murle from Boma Plateau, which he frequently visited. In 1934, he joined the maternal relatives on a raid against the Kichepo (Kachipo), also living on the Boma Plateau. In 1936, Ilemi again visited his Murle friends and was killed, but the Anuak (Anyauk) and the Murle retaliated in April of the same year, defeating the Kichepo. In June 1936 the Boma was occupied by troops from the Equatorial Corps of the Sudan Defence Force.7

The colonial authorities had this kind of unfounded description of the area which contributed negatively to the occupation and setting up of the administrative posts. According to Robert O. Collins (1983:108) “The country between Lolimi and Moru Agippi appears entirely useless. It would grow nothing and could never support a population. Water is practically non-existent and other grazing is poor. It is intensely hot and shadeless. Cotton soil, thorn bush, straw-like grass and open mudflats comprise the whole country

… a heap of sand and stones”.8 The views were based on the several factors that were prevailing at the time of the brief visit to the area and which include limited technology at the time in terms of drilling boreholes, lack of roads and Eurocentric attitude towards some of Africa’s climatic conditions.

The Delimitation of the 1914 Uganda Line

At the turn of the 19th century, when the European colonial powers were scrambling for Africa, King Menilik II of Ethiopia was also expanding his area of influence into the region south and west of his country. The British, having established a foothold in British East Africa (Kenya) and the Uganda Protectorate, were apprehensive about the Ethiopian motives. The principal factors which influenced British expansion into the region were firstly, the Ethiopians were laying claims to the region of Turkana and Karamojong. Traders and the Ethiopians obtained ivory from the Turkana by bartering with firearms, which the latter used with intense ferocity to raid other tribes (Barber 1968)9. Secondly, there was concern that the Turkana threat was forcing other groups southward, thereby posing a serious challenge to settlers in the White highlands (Muller 1989)10. Establishment of British administration in Turkana was thus aimed at counteracting the Ethiopian expansion. This imperial rivalry had an important consequence on land use and the socio-economic well-being of the Turkana and the peoples of the Lake Turkana Basin at large.

Britain disagreed with Menelik’s proposal and insisted on running the Ethiopia-Kenya boundary. Britain delineated its territories to halt other Europeans’ territorial ambitions and more specifically to curtail Emperor Menelik’s claim to land Britain considered within its sphere of influence. Mr. Archibald Butter and Captain Philip Maud surveyed Ethiopia’s border with British East Africa in 1902-3 and marked the ‘Maud line’ which was recognized in 1907 as the de facto Kenya-Ethiopian border.11

In 1907, the Anglo- Ethiopia signed the Treaty which finally halted the advance of Emperor Menelik II further south. The boundary between Ethiopia-Kenya-Sudan ran as follows:

“… to the creek at the south end of Lake Stefanie, thence due west to Lake Rudolf, thence north-west across Lake Rudolf to the point of the peninsula east of Sanderson’s Gulf, thence along the west shore of that peninsula to the mouth, or marches at the mouth, of River Kibish (River Sachi), thence along the thalweg of this river to latitude 5°25’ north: from there due west to a point 35°15’ longitude east of Greenwich, thence the line follows this degree of longitude to its intersection of the 6° north latitude with 35° of longitude east of Greenwich.”12

Having settled the Ethiopia issue, Great Britain was yet to address a similar problem within her own colonies of Uganda and Sudan. In 1913 the British authorities in Uganda and Sudan finally decided to rectify the existing border drawn arbitrarily on a map in 1902 along the parallel of 5° north latitude from the Nile east to the Omo River to identify that area in Sudan between the Toposa heartland in the west (30° 31’ east longitude) to the un-demarcated Ethiopia boundary to the east the Sudan-Kenya-Uganda boundary in the south (4°37’ north latitude).13 According to the recommendations presented by Viscount Kitchener, British Agent and Consul-General in Egypt, Cairo No. 88; May 19, 1914, to the Under Secretary of the Colonies in London; the Sudan-Uganda Boundary is described as follows:

“The boundary begins at a point, on the shore of the Sanderson Gulf, Lake Rudolf, due east of the northernmost point of the northernmost crest of the long spur running north from Mount Lubur; thence it follows a straight line to the northernmost point of the northernmost crest of the long spur running north from Lubur; thence a straight line or such a line would leave to Uganda the customary grazing grounds of the Turkana tribe, to the northernmost point of the northernmost crest of the long spur running north-west from J. Mogilla; thence a straight line in a southwesterly direction to the southernmost direction to the southernmost point at the bottom of J. Harogo; thence following a straight line to the summit of J. Latome …”14

These recommendations of the 1913 Sudan-Uganda Boundary Commission were embodied in an Order in Council by the Secretary of State for Colonies in 1914 which came to be known as the “1914 Uganda Line” – confirming the international boundary between Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Uganda, British East Africa Protectorate and Ethiopia.

On February 1, 1926, Rudolf Province (Uganda Eastern Province) was transferred from Uganda to Kenya by the Kenya Colony and Protectorate Boundaries, Order in Council, 1926. This action automatically made the 1914 Uganda Line between Zulia Mountain and Lake Rudolf the Anglo–Egyptian Sudan – Kenya boundary15 as the international boundary between the two colonies that have become neighbours. Prior to the transfer of the Eastern Province, the British East Africa Protectorate (Kenya) was not sharing any boundary with the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan as Uganda’s Eastern Province (Rudolf Province) was the sovereign territory of Uganda until it was finally ceded to Kenya on the mutual ground between the two colonies of the British Empire.16

The Red Line

“The Red Line”, sometimes called the “Thompson Line”, was invented by Captain V. G. Glenday, the Assistance District Commissioner for Turkana District to demarcate the limits of the Turkana grazing grounds.17 The idea of an “administrative” rather than an international boundary to recognize Turkana needs while not raising the thorny questions of sovereignty was first suggested by Captain V. G. Glenday in 1926. During his reconnaissance of Turkanaland, he unilaterally fixed the northern limits of Turkana grazing from Kamathia Pass southwest to the Lotagipi swamp18.

Mr. A. M. Champion, the Provincial Commissioner, Turkana, had suggested just an “administrative” boundary, the Red Line when Captain G. R. King, District Commissioner, Kapoeta had visited Lokituang after his Ilemi reconnaissance in 1931.19 There was never any correspondence between the Sudan and Kenya governments concerning such a line, it was drawn in red, naturally, on the maps and regarded as a working administrative boundary by the Kenya frontier officials and Captain G. R. King.20 The first time this arrangement at the local level was brought to the attention of the Colonial Office was on June 18th 1937 when Mr. Turnbull, the Provisional Officer, Turkana District secretly forwarded a map of the Red Line to the Colonial Office (CO533/537/18 ‘Description of the Red Line’).21 This arrangement was only an initiative of the local administrative officers in 1931 to address the needs of the Turkana to have access to grazing grounds and waterholes during dry seasons and also curb the rampant cattle rustling and raiding between the Turkana, Dassanetch, Nyangatom and Toposa.

The Green Line

Within six months after the creation of the Red Line, the Kenya authorities sought to further modify the Red Line in August 1932 to include the waterholes of Adingatom and Loruthethekon (Lorus-ethekon) west of the Kamathia Pass. To do so, the Red Line was to be redrawn north of Lorienetom and known as the “Green Line.”22 The Sudan authorities felt suspicious of the continuous expansion of Kenya into Sudan on the pretext of protecting the Turkana grazing grounds and waterholes. In a letter to his counterpart in Kenya, L. F. Nalder, Governor of Mongalla Province foresaw instant trouble around those waterholes and clearly stated as follows:

“I have little doubt that the marilli (Marille) regard the plains north of Kamathia between that Pass and that of the Donyiro (Nyangatom) Mountains as their particular grazing ground and any movement of Turkana north of Kamathia is practically certain to provoke attack” (Nalder to MacMichael, September 27, 1933, Equat. 11/37/130.).23

While Sudan was concern about the continuous expansion of Kenya into her territory, the unprecedented drought in the Turkana forced the Governor of Mongalla Province to grant temporary permission sought by the Kenya government to allow the Turkana to use the grazing grounds to the north of the Red Line with the following stipulations24:

- The approval given must not be regarded as a precedent.

- The Sudan government would accept no responsibility for the possible offensive action by the tribes grazing in the eastern Ilemi.

- The Turkana must not encroach on the grazing and watering places of the Merille.

- On the expiration of the emergency, a complete withdrawal must be made.

Robert O. Collins (1983:111) pointed out that, “although L. F. Nalder in Mongalla continued to fret over the Green Line, the remoteness of Ilemi and the realities of Ilemi Triangle which is characterized by harsh climatic conditions coupled with the realities of Turkana grazing made it a workable arrangement for the Kenya frontier officials operating in Sudan. None of these understandings was ever discussed with the Colonial Office or Foreign Office in London, and the Governor of Kenya, Sir Joseph Byrne, was empathetic in referring to the continuous expansion of the administrative boundary “as a purely temporary expedient”(Sir Joseph Byrne to Colonial Secretary, Sir P. Cunliffe-Lister, August 1, 1934, Turk./54.).25

However, it should be recalled that by the eighteenth century the Turkana split due to ecological and demographic pressures and the need to dominate trade in ironware and grain. They expanded east into Lake Turkana, south into Turkwel and Kerio valleys, and northwards into Sudan. [Mburu N. (2001) Firearms and Political Power: The Military Decline of the Turkana of Kenya 1900 – 2000. Nordic Journal of African Studies 10(2): 148-162 (2001) University of London, United Kingdom.].

This expansion further northwest and north beyond the entry of Omo River into Lake Rudolf by the Turkana happened after the international boundary was already delimited in 1914 between Uganda and the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

Prior to the transfer of the Rudolf Province (Uganda’s Eastern Province) on February 1, 1926, to Kenya, the British Colonial authorities were facing a number of problems with the Turkana. The militarization of the Turkana as from the onset of 1900 was not only a threat towards to expansion of the British Empire but a serious matter in the stability of the region. As Nene Mburu noted, “in recent times the Turkana have rearmed and expanded into areas that are strictly speaking not their ancestral pasturage but the expansion has been the initiative of elements of isolated territorial sections and not a corporate manoeuvre by the whole ethnic community” (Mburu, 2007:14). The Turkana first arrived to the northern frontier in 1915 after they were push back from the south by the King’s African Riffles (K.A.R) following their aggression as they were pushing the communities further southward towards the White Highlands which the British have settled and invested in agricultural production.

Conflict over the Ilemi Triangle

The Ilemi became a reality at a conference conveyed at Kitgum in Uganda in April 1924 on Uganda, and Sudan on the initiative of Kenya officials and attended by representatives of Kenya, Uganda and Sudan. According to the report of Major R. G. C. Brook, “The problem was the safety of the North Turkana”; the Kenya initiative was to control the Ilemi Triangle (Major R.G.C. Brook, Deputy Governor, Mongalla Province, “Report on Kitgum Conference 1924, Equat. II/37/130, in Robert O. Collins, 1983).26 During the conference, the Kenya representative at Kitgum suggested obvious solutions: Firstly, the cession of the Triangle to Kenya; Secondly, Sudan to make a financial contribution to the expenses incurred by Kenya administering its territory on its behalf – Ilemi Triangle and finally, Sudan to occupy and administer the Toposaland west of the Triangle. Sudan was represented in the conference by Major R. G. C. Brook, Deputy Governor of Mongalla Province who had been instructed only to discuss military cooperation against raiders with the counterparts.

Although the Sudan government was not willing and ready to occupy the country of Toposa and sets its administration along the international boundary with Kenya and Ethiopia as a result of several failed attempts to establish military garrisons in the country of Toposa due to hostile nature of the Toposa

warriors who inflicted loses against the invading troops, these demands were further strengthened by the reports in 1925 of additional raids upon the Turkana in Sudan by the Dassanetch. Out of pressure from Uganda, Kenya and Colonial Office, the Sudan government in Khartoum gave permission to Kenya authority to cross to the border to exact retribution from the Dassanetch, but the Governor-General in Khartoum, Sir Geoffrey F. Archer, sardonically suggested that “the best safeguard for Turkana would be to stay on their own side of the Kenya-Sudan border under the cover of KAR posts. In any case, Sudan administration must exclude Ilemi Triangle … because of the problems of supply … and prohibitive costs” (Sir Geoffrey Archer, Governor-General, to Robert T. Coryndon, Governor, Kenya, June 20, 1925, tel. 849, Int. I/7/32).27 It is important to correct the statement put forward by Nene Mburu in which he referred to Sir Geoffrey Archer as, “a Kenyan colonial official”(Mburu, 2007:114). Sir Geoffrey Francis Archer was the Governor-General of Sudan as from January 5th 1925 to July 6th 192628.

In December 1931, Sir John L. Maffey, The Governor-General of the Sudan, after submitting the terms of agreement to the British High Commissioner for Egypt and the Sudan in Cairo informing him that as a result of the negotiations held in London on July-August 1931, the Sudan Government undertook to pay a sum of £10,000 in the year 1932 as a non-recurrent contribution towards the military expenditure for the defence of the Turkana which would be shared by the Kenya and Uganda governments, and in addition, a further sum of £5,500 to cover the cost of roads from Moroto to Lorugumu, and from Narumum to and over the Kamathia and Lokitoi Passes which are to connect Turkana with the administrative centres of the Kenya Governments and Uganda. At the end of these lengthy negotiations, the governments of Kenya and Uganda accepted the Sudan government’s offer (C.O. 533/406/8, a telegram dated September 4th, 1931, the Governor of Kenya to the Secretary for Colonies accepting the agreement reached with the Sudan Government).

The Sudan Government stated that until then the Sudan Government and Kenya Government had not seen matters in the Ilemi Triangle eye to eye, for although part of the Triangle is valuable for the Turkana in the years of drought, the refusal of Kenya to take the administrative liability of the area at their own cost irritated the Sudan Government. Sudan had never admitted any Kenyan rights, nor had Kenya admitted any liability north of the international frontier (C.O. 822/89/9, dispatch No. 43, 93.H.1, dated March 30th 1938, to the British Ambassador, Cairo.)29. Upon accepting the conditional contribution from the Sudan Government, the Kenya and Uganda governments indicated that they reserved the right to raise the issue again should there be any recurrence of raids originating or passing through Sudan territory (C.O. 533/406/8, a telegram dated September 4th, 1931, the Governor of Kenya to the Secretary of State for Colonies noting this reservation).

The critical question one should ask in regard to the attitude of Uganda and Kenya towards the administration of the boundary is mind-boggling. Firstly, both Uganda and Kenya authorities were contented with the international boundary which was adopted in 1914; secondly, the problem was the Turkana of Uganda’s Rudolf Province and later of Kenya’s Turkana District who was trespassing into Sudan’s territory in search of pasture and water and while at the same time exerting aggression against the neighbouring tribes of Marille and Nyangatom in Ethiopia, Toposa and Nyangatom in Sudan by raiding their cattle and pushing them further west and north of the Ilemi; thirdly, why should Sudan bear the financial costs of protecting the Turkana by paying an annual fee to Kenya authorities to set up administrative posts in Sudan’s jurisdiction for the protection of their own citizens within the territory of Sudan? Looking into this scenario, the predatory attitude of Kenya and Uganda which we the people of South Sudan see today was nurtured right from the Kitgum Conference of April 1924.

The British dominant position in Sudan had been formalized in the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1899, which recognized Sudan as an Egyptian possession administered by the British officials on behalf of the King of Egypt (Johnson. H. Douglas, 2011:21). This Treaty implies that any major decision affecting the sovereignty of Sudan must be accepted and approved by Egypt.

The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Sudan was the largest of the political units created by Imperialism in Africa with an overall size to just one million square miles (2.4 million square kilometers)30. This meant that for the entire territory to be administered effectively, huge resources were needed to do so.

In 1937, the Foreign Office in London, acting in the interest of Egypt and Sudan, considered a major boundary rectification with Italian East Africa Ethiopia, which for administrative convenience would involve the cessation of the whole of Ilemi triangle to Ethiopia in return for the Baro Salient. At the request of the Colonial Office, a map and the description of the revised Red Line was forwarded by Kenya in a secret dispatch of June 18th, 1937. Mr. Turnbull, the Provisional Officer, Turkana, noted that it was the first occasion on which the Red Line had been officially brought to the notice of the British Government; it had started as an arrangement between neighbouring administrative officers and had never reached the status higher than that of local agreement (C.O. 533/537/, Turnbull, R. G., Memorandum on Turkana Frontier Affairs, 1944.)

Having been notified of the Sudan Government’s intention to cede Ilemi Triangle, the Government of Kenya requested a boundary adjustment of its border with Sudan to include the Turkana grazing grounds permanently in Kenya as a pre-requisite to its consent to any boundary rectification between Sudan and Ethiopia which might involve the cessation of Ilemi Triangle (C.O. 822/89/9, dispatch No. 43, 93.H.1, dated March 30th 1938, to the British Ambassador, Cairo.)31. The dispatch from the Governor of Kenya to the Colonial Office of September 1st, 1938 enclosed in Mr. Eden’s Dispatch No. 1103 (J. 403/47/1) of September 30th, 1937, states that it is only in the event of the Ilemi Triangle being ceded to Italy that an adjustment of the Kenya-Sudan Boundary is regarded as essential. In these circumstances, it seems clear that the government of Kenya require before the opening of the negotiations with Italy is a definite agreement that the Sudan-Kenya adjustment will take place on the successful conclusion of negotiations with Italy (46598 G/38 No. 11, 1st Enclosure No. 411 – Secret)32. The attempt to exchange the Baro Salient with the Ilemi Triangle came to a non-conclusive end when Italy was defeated on April 6th 1941 and that ended the two years’ brief occupation of Italy over Abyssinia.

The Toposa Question 1912 – 1927”: Conquest and Establishment of Administration

The British Colonial Administration knew little about the Toposa. According to Robert O. Collins (The Toposa Question, 1981 – 1982)33 “The Toposa first emerged in British consciousness in 1912, when the Governor of Mongalla, R. C. R. Owen, was cordially received by the influential elder Tuliabong during a punitive patrol against the Murle of the upper Pibor.”

The question about the Toposa arose as the result of several attempts by the British officials to establish a foothold in Toposaland which resulted in devastating defeats of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan army by the Toposa warriors. The defeat of the British Forces at Losinga in 1920 as they were attempting to establish a garrison and the withdrawal of the troops from Khor Locheriatum following the fight between Toposa herdsmen and the troops resulting to fruitless Patrol and loss of lives on both sides and among herdsmen, the death of Lomoti – the son of the most influential Toposa elder was treated as an insult, a sign of weakness and vacillation of the British Forces. In his report to Civil Secretary, Governor V. R Woodland at Mongalla expressed the local point-of-view when he wrote:

All recent reports of “the Toposa” attitude towards the government indicate that they must be broken before they will submit to control. Nothing is to be gained by visiting them unless the government intends to occupy and administer their country … any merely temporary advance … even a route march … is to my mind undesirable. And any such advance resulting in unfriendly and perhaps insulting treatment of the troops by the local people followed by retirement would be folly” (The Toposa Question, 1912 – 1927, Northeast African Studies, 3.3 (1981- 82) University of California, Santa Barbara) 34

In contrast to the view put forward by Governor V. R. Woodland, Jack H. Driberg, Commissioner of Eastern District of Equatorial Province at Nagichot sought to use a different tactic by employing Harold McMichael’s principal argument at the Foreign Office in hope of extracting permission to move against the Toposa:

“I understand that my present instructions are not to risk a conflict with the Topotha by visiting their country. While I appreciate the motives of this policy, I venture to submit that it is mistaken, that it leaves the Topotha completely at the mercy of the poachers in Abyssinia and the consequence is that an act of anti-British propaganda is being carried on which is bound to neutralize my attempts at peaceful persuasion, and what is even of greater importance, a large number of rifles and a quantity of ammunition is being imported”35 (Governor, Mongalla Province, V.R. Woodland to Civil Secretary, January 18, 1921, enclosed in Skrine “Note on Past Policy Regarding Topotha,” Mongalla, 1/6/38. CRO).

Finally, on December 18, 1926, two companies of the Equatorial Troops under Captain E. Knollys moved from Loriyok Post and pushed eastward into Toposaland, reached the Thingaita River on January 5, 1927, and established a post at Kapoeta on the east bank. This date marked the occupation of the Toposaland by the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

The Sudan Patrol Line

Sudan, in 1950, established their own patrol line at Loele and Kibish, and even further northwest into Sudan were they prohibited Kenyan and Ethiopian pastoralists from moving west of it, giving up policing and development to the area east of it. However, that Kenya-Sudan agreement specified that this patrol line in no way affected sovereignty; that it was not an international boundary, and money continued to be paid to Kenya to patrol this Sudanese territory.

The Legal Arrangement over the Administration of the Ilemi Triangle by the two Governments

The establishment of administrative police posts by Kenya government ‘beyond their frontiers’ with the permission from the Government of Sudan could not add to any Kenya claim for the cession of any part of Ilemi Triangle. It is important to note that the presence of Kenya inside Sudan was based on continuous mutual agreement between the two countries to create an order using the laws of Sudan. According to Tungo, A. M. (2008:112), “Explicitly, Kenya’s permission to administer the area did not entail extending Kenyan legal system over Ilemi, far from that Sudan legal system was one applicable”. In administering the area, Sudan used the Kenyan administrator and Law Enforcement Agencies to exert and exercise its rule in the Ilemi Triangle.

While Kenya was reluctant to administer part of the Ilemi Triangle and at the same time requesting for the annexation of the area as part of her sovereign territory, as they were alleging that the Governor-General of Sudan had accepted the Wakefield Line of 1938 as the de jure boundary; the Colonial Office on February 27th 1958, the replied stating the arrangement as follows: “… impression was that it was agreed only as an administrative boundary, and point clearly out clearly that there was no explicit acceptance of the line by the Governor-General as the de jure frontier” (Hertslet, The Map of Africa by Treaty (1907) Vol., 103, p.445; quoted in Tungo, A. M. (2008:117). The rejection of Kenya request for the cession of part of the Ilemi Triangle was consistent with the one made in 1938 as follows:

“While it is clear that there can be no question of cession to Kenya of any part of the Ilemi Triangle, there is no reason why the Government of Kenya should not administer the territory up to the Blue Line, in addition to that it already administer, provided that the Sudan Government agree … As these arrangements between the two countries are purely administrative one, and there is no question of sovereignty involved” (C.O. 822/89/9, letter No. 50, dated October 10th1938, Under Secretary of State for the Colonies to the Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, quoted in Tungo, A., 2008:89).

The argument put by Kenya in their claim on the area for having maintained the frontier posts within the Ilemi Triangle from 1926 without any objection nor financial and personnel contribution from Sudan is contrary to the arrangement that was used to administer the area. Records attest the appointment of personnel by Sudan Government and the application of Sudan’s laws in the Ilemi Triangle. For example,

Magisterial appointment dated January 16th 1946, Khartoum issued by the Legal Secretary, Sudan acting as Governor-General, reads: “I hereby appoint Lieutenant Commander Denis Mackay, Royal Navy (Retired) District Commissioner Turkana, to be a magistrate of the First Class under the Code of Criminal Procedure with jurisdiction in the Eastern District of Equatoria Province … Also Mr. Peter Guthrie Tait, District Officer, Lokituang, was appointed as a magistrate of the First Class”36 clearly proof beyond doubt the exercise of Sudan’s legal instruments over her own sovereign territory using Kenya to do so. It is also to note that:

“Kenya officials appointed as magistrate by the Sudan Government were supplied, by the Sudan Government with several parts of the new Sudanese Legislation relevant to their position. This includes the Sudan Penal Code, The Code of Criminal Procedure, Title III of the Laws of Sudan which contain the Police Ordinance of 1928 under which appointments of Kenyan official as magistrates were made, and the Passports and Permits Ordinance under which unauthorized entry into Sudan was prohibited”37

The Sudan Legal Secretary acting for the Governor-General issued an order for the adoption of the Kenya Police Force to carry out Law and order on behalf of Sudan as follows:

“In exercise of his powers under section 4 of the Police Ordinance 1928, the Governor General hereby orders that in the Eastern District of Equatoria Province, the Turkana Unit of Kenya Police, the Lokituang Tribal Police and the Turkana Frontier Tribal Police shall be deemed to form part of the Sudan Government Police Force with the duties and obligations prescribed by section 6 and 11 of the Police Ordinance 1928 And all the powers and duties of Police under the Code of Criminal Procedure and any other ordinance or regulations”38

The exercise of powers by the Kenyan Magistrates appointed by the Sudan Government in accordance with the Sudanese Laws was made clear. In a letter dated January 21st 1946 Mr. G. M. Hancock, the then Acting Civil Secretary, Sudan, to Chief Secretary, Colony and Protectorate of Kenya explained that:

“It is envisaged that should the Kenya police have in accordance with your instructions to arrest any uniformed Ethiopian, the Magistrates before whom such an arrested person would be taken as laid down in the instructions would be one of the Kenya officers who are now appointed as Sudan Magistrate for the purpose, but after conviction and sentence of imprisonment, should this occur, the prisoner would be handed over to the District Commissioner of Eastern District of Equatorial at Nagichot or to his representative elsewhere in the Eastern District as might be agreed for the occasion, for custody in Sudan”39

The Sudanese Legislation also applied to the Kenyan Turkana tribesmen during their stay in the area. As late as 1958, convicted criminals in the Ilemi Triangle were surrendered to the Sudanese authorities in Equatoria. For example, in 1958, three Turkana tribesmen were arrested at Lokituang by the Turkana Frontier Tribal Police for the murders they committed against the Toposa of Sudan during the Turkana raid inside Sudan which left a number of people dead. The three men were handed over to the Commissioner of Kapoeta District after the death sentence was passed to them at Lokituang for execution. But among the 3 men was a young boy by the name Ngikoi who was underage. The two men were then executed at Moru ka Eris military range ground by firing squad and Ngikoi was spared of death sentence and sent to Port Sudan to serve his prison term. He would later be released and become one of the most influential chiefs of the Turkana in Turkana District.

The British’s Government Position on the Administrative Nature of Ilemi Triangle

In 1966, the Director of Kenya Surveys during the Presidency of Jomo Kenyatta’s administration had made overtures to the British in order to secure support for the recognition of the part marked by the Red Line as Kenya international boundary with Sudan. In response to his request for the acceptance of Red Line as the international boundary between Sudan and Kenya, Mr. R. T. Porter, the Director of Overseas Surveys in England responded to his letter Reference: 1048/4/1 CG/30/15 dated 28thAugust 1966 as follows:

“… it is our view that the actual adoption of the alternative of 1914 was contingent upon certain other events which were expected to occur just before the last war; the proposed boundary was surveyed in 1938 (not 1935) in anticipation. However, although the then Sudanese and Kenyan Governments were authorized in 1939 by His Majesty’s Government to accept and refer to the Red Line as the Provisional Administrative Boundary, the line never received full recognition from all those concerned. Accordingly we feel we cannot show on our maps the Red Line as the accepted international boundary, on the information at present available to us.”40

In his reply to these enquiries, Sir Mile Lampson, the British Ambassador in Cairo (1936 – 1946) writing to the Colonial Office in London, responded to the request for the publication that includes the area administered by Kenya on behalf of Sudan as part of Kenya pointing that:

“The frontier should not be marked on any published maps before the revision of this frontier is explained to the Egyptian and Italian Governments. Moreover, the view hitherto adopted in correspondence on this subject is that the adjustment of the Sudan-Kenya border would not be effective until the negotiations with the Italian Government have been completed. It, therefore, appears that the marking of the new frontier awaits not only the opening of the negotiations with Egyptian and Italian Governments, but the successful conclusion of these negotiations” (F.O.371/69291, Records of discussions dated January 20th 1948, between Mr. Spraight, Cairo, and Mr. Robertson, of the Colonial Office quoted in Tungo, A. 2008:84-85).

The consistency of the British Government with respect to the international treaty that defines the boundary between Sudan and Kenya remained unchanged. The idea of ceding part of the Ilemi Triangle to Kenya in 1938 was conditioned on the outcome of the proposed exchange of the Baro Salient which did not materialize as a result of the defeat of Italy in 1941 that ended the brief Italian rule in Abyssinia.

Conclusion

According to Nene Mburu (2007:180) “… Sudan has all along accommodated Kenya’s unilateral management of the Red Line, this and the 1950 Sudan Patrol Line could not be taken to be mutually agreed on grazing arrangements to assume security for Turkana herders, which Khartoum could not guarantee. In this case, Kenya may have gone a step too far to assume that an administrative boundary, in this case, a mutually established grazing unit, could supersede the international boundary (1914 Uganda Line) without engaging the due process of a mutually negotiated and agreed boundary order in council or international treaty agreement”. Thou Kenya has taken the Red Line as an international boundary as it appears in Google Maps and in the Global Positioning System (GPS), this should be treated as Google’s Boundary that cannot confer any legitimacy to Kenya over the territory of Sudan (South Sudan) for the current time.

Finally, I would like to pick a quote from the International Crisis Group (ICG) (4 April 2002: i-ii) as quoted in Teshome, B. Wondwosen (2009, p. 353) that:

“The failure to resolve border issues prevents neighbours from normalizing relations and dealing with pressing social and economic issues. Thus it is important that any territorial differences be resolved on a mutually acceptable basis in accordance with the standards of international law and practice.”

The current diplomatic effort between the two Governments of the Republic of South Sudan and the Republic of Kenya should be reminded that no territorial land as per the International Treaties can be ceded away to another sovereign state without opened and public agreement from the citizens as a gesture of good relationship between parties.

About the Author

Michael Lopuke Lotyam is a Former Minister of Education in Eastern Equatoria State and former Undersecretary of the National Ministry of General Education and Instruction in the Republic of South Sudan. He obtained his Master of Science Degree in Social Development (and Policy Management) at the University of Swansea, South Wales – the United Kingdom in 2009; and Bachelor of Science at the Catholic University of Eastern Africa, Nairobi – Kenya in 2006.

References

1 John Ryle et. al. (2011) The Sudan Handbook

2 Johnson. H. Douglas (2011) The Root Causes of Sudan’s Civil Wars: Peace or Truce, Revised Edition: James Curry 3 Robert O. Collins (1983) Shadows on Grass: Britain in the Southern Sudan, 1918-1956. Yale University Press: New Haven and London.

3 Robert O. Collins (1983) Shadows on Grass: Britain in the Southern Sudan, 1918-1956. Yale University Press: New Haven and London.

4Teshome, B. Wondwosen (2009) Colonial Boundaries of Africa: The Case study of Ethiopia’s Boundary with Sudan.

Ege akademik Bakis/EgeAcademic Review 9(1) 2009:337-367)

5 Tungo A. Muaz (2008) The Ilemi Triangle: Sudan-Kenya Disputed International Boundary, Khartoum University Printing Press

6 Robert O. Collins (1983) Shadows on Grass: Britain in the Southern Sudan, 1918-1956. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

7 ibid

8 General Report by Political Officer Lolimi to Moru Agippi by Captain G. R. King, January 15, 1931, Mon. 1/2/13 in

Robert O. Collins (1983) Shadows on Grass: Britain in the Southern Sudan, 1918-1956. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

9 Barber, J. (1968) Imperial frontier: A study of relations between the British and the pastoral tribes of North East Uganda. East African Publishing House.

10 Muller, H.K. (1989) Changing Generations: Dynamics of Generation and Age-Sets in south eastern Sudan (Toposa)

and Northwestern Kenya (Turkana).

11 Edward Waithaka and Patrick Maluki, (2016) Emerging Dimensions of the Geopolitics of the Horn of Africa:

International Journal of Science Arts and Commerce Vol. 1 No. 4, June-2016

12 Tungo A. Muaz (2008) The Ilemi Triangle: Sudan-Kenya Disputed International Boundary, Khartoum University Printing Press

13 Ibid

14 Viscount Kitchener, British Agent and Consul-General in Egypt, Cairo No. 88; May 19, 1914; to the Under Secretary of the Colines, London on Sudan-Uganda Boundary

15 Waithaka E. and Maluki, P. (2016) Emerging Dimensions of the Geopolitics of the Horn of Africa: International

Journal of Science Arts and Commerce Vol. 1 No. 4, June-2016.

16 Nene Mburu (2007) Ilemi Triangle: Unfixed Bandit Frontier Claimed by Sudan, Kenya and Ethiopia. Published Vita House Ltd.

17 Robert O. Collins (1983:109) Shadows in the Grass: Britain in Southern Sudan, 1918-1956. Yale University Press,

New Haven and London

18 Captain V. G. Glenday, “Marille Patrol, November-December 1926,” Turk,/54 in Robert O. Collins (1983)

19 Ibid

20 King to L. F Nalder, Governor, Mongalla Province, December 18, 1937, Equa,11/37/130 in R. O. Collins (1983:109)

21Nene Mburu (2007) Ilemi Triangle: Unfixed Bandit Frontier Claimed by Sudan, Kenya and Ethiopia. Published Vita House Ltd.

Tungo, A. M. Muaz (2008) The Ilemi Triangle: Sudan –Kenya Disputed International Boundary; Khartoum University Printing Press.

22 R.O. Collins (1983) Shadows in the Grass: Britain in Southern Sudan, 1918-1956. Yale University Press, New

Haven and London

23 Ibid

24 C.O. Letter No. dated from Governor-General, Khartoum, to Governor of Kenya, Nairobi; in Tungo, A. M. Muaz (2008) The Ilemi Triangle: Sudan –Kenya Disputed International Boundary; Khartoum University Printing Press.

25 Ibid

26 R.O. Collins (1983) Shadows in the Grass: Britain in Southern Sudan, 1918-1956. Yale University Press, New Haven and London

27 ibid

28 Sir Geoffrey Francis Archer – The British Empire access in https://www.bitishempire.co.uk on 25th August, 2019

29 ibid

30 John Ryle et. al 2011 The Sudan Handbook.

31 Tungo, A. M. Muaz (2008) The Ilemi Triangle: Sudan –Kenya Disputed International Boundary; Khartoum University Printing Press.

32 ibid

33 The Toposa Question, 1912 – 1927, Northeast African Studies, 3.3 (1981- 82) University of California, Santa Barbara

34 Governor, Mongalla Province, V.R. Woodland to Civil Secretary, January 18, 1921, enclosed in Skrine “Note on

Past Policy Regarding Topotha,” Mongalla, 1/6/38. CRO

35 Ibid

36 ibid

37 Tungo, A.M. Muaz (2008)

38 Foreign Affairs Ministry Minutes of Sudan-Kenya Boundary Commission meeting Nairobi January 15-21, 1982

quoted in Tungo, A. M. Muaz (2008) The Ilemi Triangle: Sudan –Kenya Disputed International Boundary; Khartoum University Printing Press.

39 Foreign Affairs Ministry Minutes of Sudan-Kenya Boundary Commission meeting Nairobi January 15-21, 1982

quoted in Tungo, A. M. Muaz (2008) The Ilemi Triangle: Sudan –Kenya Disputed International Boundary; Khartoum University Printing Press.

40 ibid